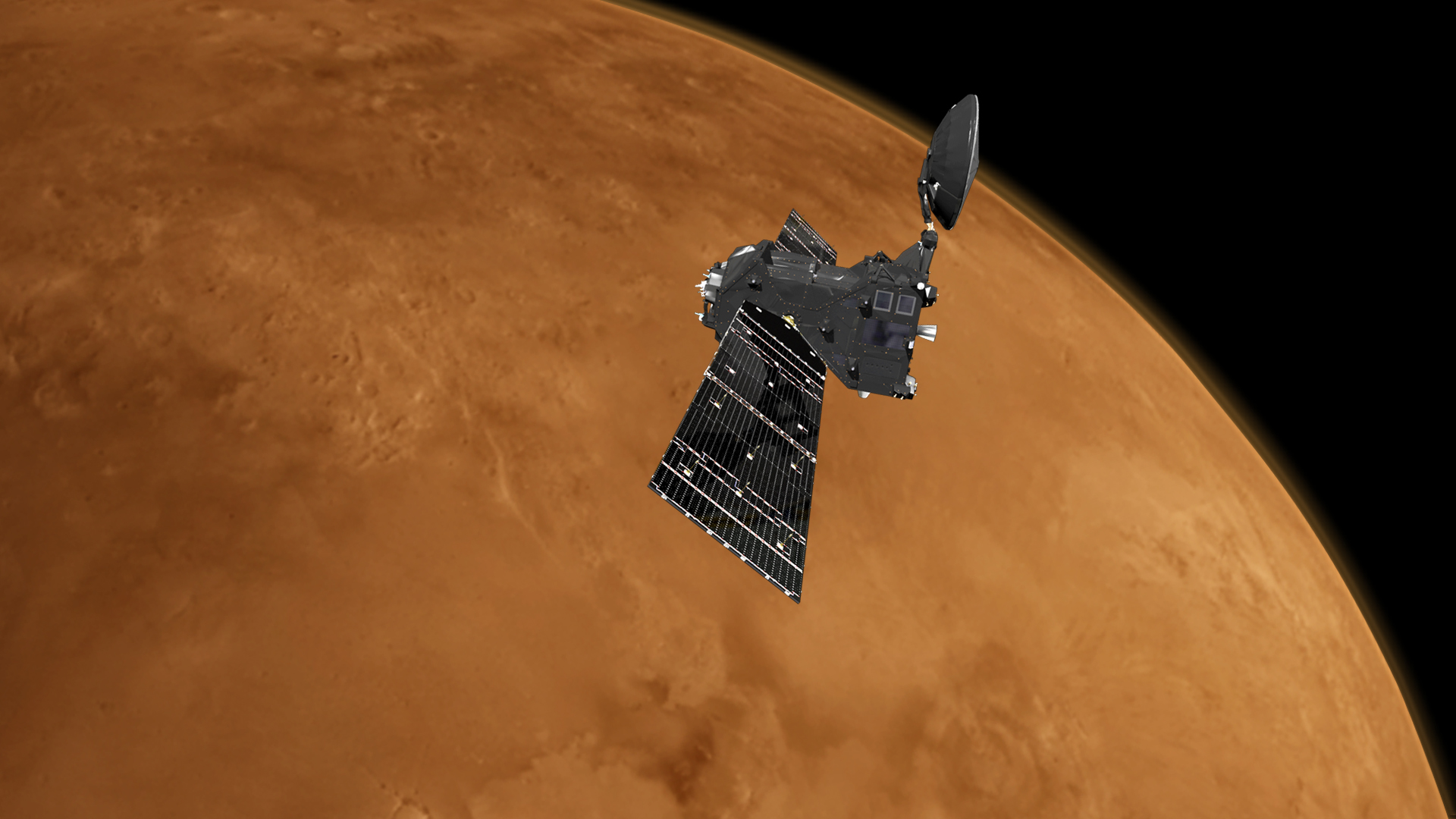

After the smooth arrival of ESA’s latest Mars orbiter, mission controllers are now preparing it for the ultimate challenge: dipping into the Red Planet’s atmosphere to reach its final orbit.

The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter is on a multiyear mission to understand the tiny amounts of methane and other gases in Mars’ atmosphere that could be evidence for possible biological or geological activity.

Following its long journey from Earth, the orbiter fired its main engine on 19 October 2016 to brake sufficiently for capture by the planet’s gravity.

It entered a highly elliptical orbit where its altitude varies between about 250 km and 98 000 km, with each circuit taking about four Earth days.

Ultimately, however, the science goals and its role as a data relay for surface rovers mean the craft must lower itself into a near-circular orbit at just 400 km altitude, with each orbit taking about two hours.

Mission controllers will use ‘aerobraking’ to achieve this, commanding the craft to skim the wispy top of the atmosphere for the faint drag to steadily pull it down.

“The amount of drag is very tiny,” says spacecraft operations manager Peter Schmitz, “but after about 13 months this will be enough to reach the planned 400 km altitude while firing the engine only a few times, saving on fuel.”

During aerobraking, the team at ESA’s mission control in Darmstadt, Germany, must carefully monitor the craft during each orbit to ensure it is not exposed to too much friction heating or pressure.

The drag is expected to vary from orbit to orbit because of the changing atmospheric, dust storms and solar activity. This means ESA’s flight dynamics teams will have to measure the orbit repeatedly to ensure it does not drop too low, too quickly.

The aerobraking campaign is set to begin on 15 March, when Mars will be just over 300 million km from Earth, and will run until early 2018.

Mission controllers are now working intensively to prepare the craft, the flight plan and ground systems for the campaign.

Late last month, they adjusted the angle of the orbit with respect to the Mars equator to 74º so that science observations can cover most of the planet.

Next, to get into an orbit from where to start aerobraking, the high point will be reduced on 3 and 9 February, leaving the craft in a 200 x 33 475 km orbit that it completes every 24 hours.

ESA mission controllers have some previous experience with aerobraking using Venus Express, although that was done at the end of the mission as a demonstration. NASA also used aerobraking to take the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and other spacecraft into low orbits at Mars.

“This will be our first time to use aerobraking to achieve an operational orbit, so we’re taking the extra time available now to ensure our plans are robust and cater for any contingencies,” says flight director Michel Denis.

Aerobraking proper will begin on 15 March with a series of seven thruster firings, about one every three days, that will steadily lower the craft’s altitude at closest approach – from 200 km to about 114 km.

Flight dynamics experts at our ESOC operations centre work on every ESA mission, from those in very low orbits, like Swarm and CryoSat, to those exploring our Solar System, like Rosetta and ExoMars.

“Then the atmosphere can start its work, pulling us down,” says Peter Schmitz. “If all goes as planned, very little fuel will then be needed until the end of aerobraking early in 2018, when final firings will circularise the 400 km orbit.”

No date has been set, but science observations can begin once the final orbit is achieved. In addition, the path will provide two to three overflights of each rover every day to relay signals.

Overall, the spacecraft is in excellent health. On 30 November, it received an updated ‘operating system’. To date, only one ‘safe mode’ has been triggered, when a glitch caused the craft to reboot and wait for corrective commands. That happened during preliminary testing of the main engine, when a faulty configuration was quickly identified and fixed.

“We are delighted to be flying such an excellent spacecraft,” says Michel. “We have an exciting and challenging mission ahead of us.”