“We can fly to Mars.”

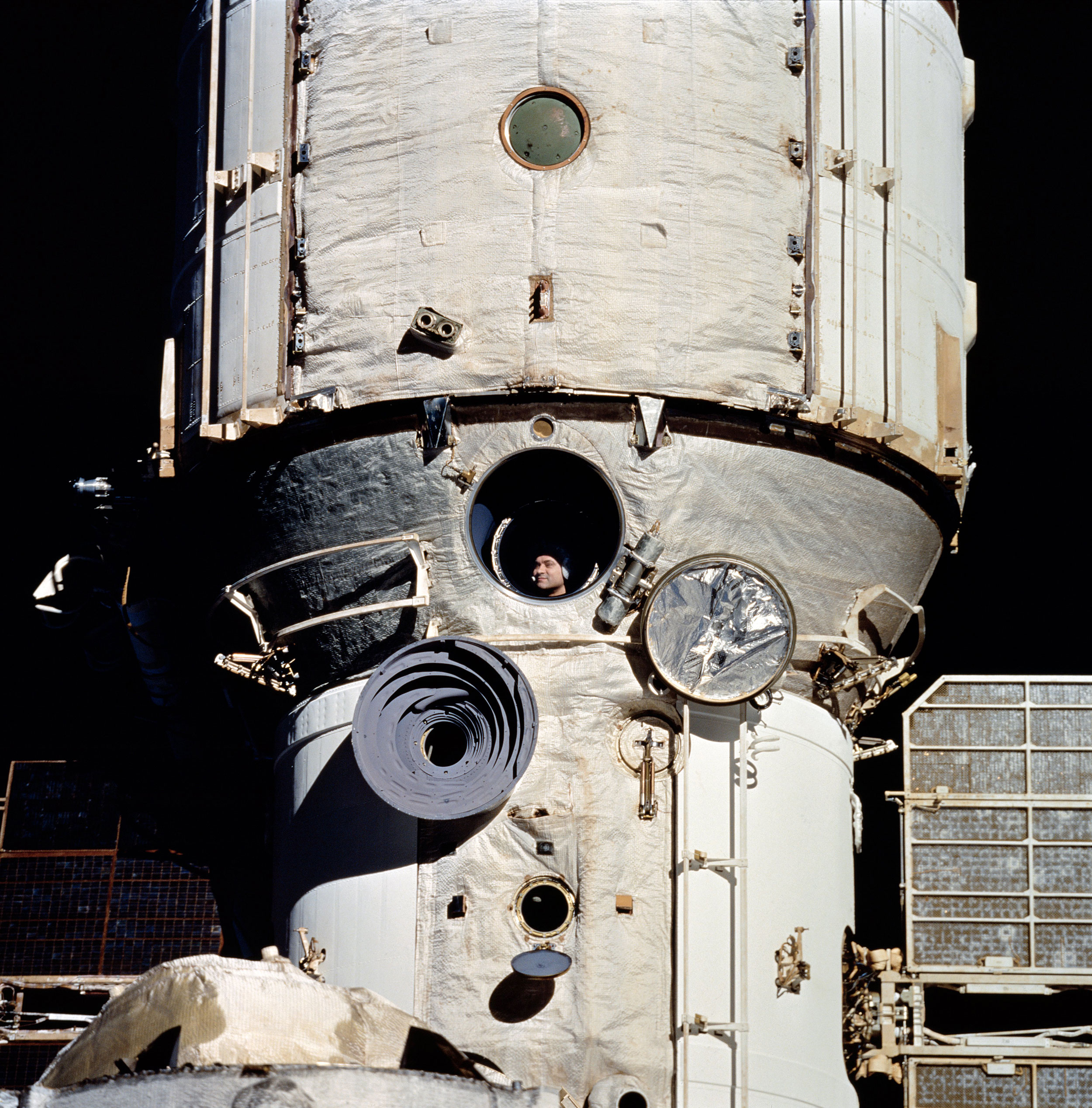

That was the first thing Valeri Polyakov said on March 22, 1995, after returning from a 437-day 18-hour stay aboard the Russian space station Mir. During those fourteen and a half months, he orbited the Earth 7,075 times and traveled nearly 187 million miles. After twenty years, it remains the longest continuous spaceflight of any individual. The idea behind that long mission was to simulate a trip to Mars.

It was a trip he had waited thirty years for. Polyakov finished medical school in Moscow in 1965, just four years after his countryman Yuri Gagarin completed the first manned spaceflight. That flight and other Soviet and American orbital flights that followed inspired Polyakov to specialize in space medicine. In 1972, he began training to monitor other cosmonauts during their flights and to prepare for eventual spaceflights of his own.

His first chance to live in space came in August 1988, when he flew to the Mir space station, which had been orbiting the Earth for over two years. He studied the effects of microgravity on himself and fellow cosmonauts during a 240-day mission.

“I felt very good during the whole flight – on the [launch], during the time on the orbit, and during the landing,” Polyakov told an oral history interviewer in 1996. “It can be explained because I am a specialist in space medicine. I know how to use the methods of control, all of the things that protect you, how to use countermeasures the best.”

In January 1994, Polyakov got his second chance to live in space aboard Mir. Originally planned for up to eighteen months, the mission length was shortened somewhat because of budget cuts and launch postponements due to rocket engine delivery delays. Until that time, the longest single mission had been 366 days 23 hours, accomplished by Vladimir Titov and Musa Manarov in 1987-88.

“My goal was to demonstrate the ability to work on Mars and come back in good health,” Polyakov said in a January 2001 National Geographic article. His compulsion to demonstrate that capability helped him convince his government to finance the project during the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the resulting economic chaos in Russia.

Polyakov told Robert Zimmerman, author of Leaving Earth: Space Stations, Rival Superpowers, and the Quest for Interplanetary Travel, that he felt very different during the launch of his second mission. “Moments before launch, Polyakov’s thoughts were far different than those on his first flight,” Zimmerman wrote. “Then he had felt eager, excited, and joyous about finally getting into space. Now he felt only fear. He wasn’t afraid of dying. Far from it. What he feared now more than anything was failure. ‘What if something goes wrong?’ he asked himself…. ‘I had sacrificed so much time,’ he thought. ‘The government has spent so much, more than they can afford.’”

But nothing went wrong. Liftoff was smooth, docking was successful, and Polyakov got to work. He and a succession of crew mates performed twenty-five ongoing experiments, mostly in life sciences. The topics included microgravity’s effects on blood chemistry and volume, the circulatory system, the central nervous system, and bone density.

Polyakov, himself, was the subject of a variety of evaluations. “Mental Performance in Extreme Environments: Results from a Performance Monitoring Study During a 438‑Day Spaceflight,” a 1998 paper he co-authored, detailed the extensive examinations he underwent before, during, and after the mission. They measured emotional moods, cognitive performance, the ability to manually track the path of moving images, and his perceptions of workload intensity.

The results were based on only one person’s responses, but they offer a glimpse of what other astronauts might experience on a long spaceflight. During the last three days before launch, Polyakov’s performance declined in cognitive tasks and tracking response rates. During the first three weeks in space and following his return to Earth – periods when he had to adapt to new environments – he experienced “considerable [reductions] of tracking performance, as well as elevated [perceived] workload ratings and clear drops in subjective mood.” However, during the second to fourteenth months in orbit, he showed “an impressive stability of mood and performance.” After the mission, there were no long-term reductions in performance.

Those carefully structured tests yielded useful results, and so did informal observations. For example, in his 1996 interview, Polyakov talked about experiencing cosmic radiation. “When you sleep at night, if the particle hits your eye, you can see the flash,” he said, “like sparks in the eye when somebody hits you in the head.”

He also experienced a common effect of long-duration microgravity. On Earth, a person’s spine is curved. Without the normal force of gravity, the spine straightens, and the distance between the discs increases. After fourteen months in orbit, Polyakov’s height increased from six feet two and a half inches to six feet five inches. That presented a problem for the trip back to Earth. “When you come back, you have to fit yourself in the chair that was made for your size as you were coming up,” he said. “If you wear a special suit, it is called ‘penguin,’ it kind of presses you down. In that case you will have less of a problem.”

Yet another informal observation came from American astronaut Norman Thagard, who arrived aboard Mir six days before Polyakov returned to Earth. “[Polyakov’s] legs were just as big as tree trunks,” Thagard told Zimmerman. “If he did that well after fourteen and a half months, I probably don’t have much to worry about for just [a few] months.”

Thagard and Polyakov were reunited in October 1996, when they were both inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame. In an oral history interview at that time, Thagard said, “Doctor Polyakov told me this morning that he only lost 12 percent of bone mineral from one of the bones that we use for study, which is exactly the same I lost from that same bone in four months [aboard Mir]. He thinks that the countermeasures he did may help limit that.”

Polyakov’s physical condition was impressive because he exercised strenuously for two hours every day during his entire mission. He knew this was important for several reasons. It helped prevent motion sickness while in orbit as well as during the reentry flight and landing. Also, he wanted to demonstrate that after a long trip to Mars, an astronaut would be in good enough shape to work on that planet.

Polyakov proved his point when he landed in Kazakhstan. As he exited the spacecraft, he insisted on walking, with some assistance, the short distance to the chairs that awaited him and his two companions. He took a drag from a friend’s cigarette and a sip of brandy offered by another. Then, after the cosmonauts were carried in their chairs into a medical tent, Polyakov stood up again and took a step or two without help. During the flight to Star City, he walked back and forth inside the helicopter, and at the end of that flight, he stepped off the aircraft and walked almost normally.

In his 1996 oral history interview, he summarized the importance of that: “I was able to come out of the capsule by myself, to walk around, to undress, to dress, to do pretty much everything. And be conscious of everything. That was pretty much the goal of the flight. I had to show that it is possible to preserve your ability to function after being in space for such a long time. But the gravity on Mars is .37. And since I was able to stand up and walk on the Earth wearing a space suit, it shows that [a] human is able, will be able to stand up and walk on Mars.”

Polyakov attained his goal of proving humans could maintain good physical condition after a spaceflight longer than would be needed to reach Mars. His oral history interviewer asked, if he had it to do over again, would he go into space for such a long mission. The cosmonaut replied, “In this century if there would be an opportunity to go to Mars, not to stay in orbit as I did, I would get permission from my wife.”

To that, his wife responded, “He just says that. He is not even going to ask.”