Perihelion: 1957 August 1.44, q = 0.355 AU

During the mid-20th Century the northern hemisphere went several decades without a bright naked-eye comet; what bright comets that did appear during that time were primarily visible from the southern hemisphere. This changed during 1957, when Comet Arend-Roland 1956h became bright and conspicuous during April and May, reaching 1st magnitude and displaying both a prominent dust tail and a distinct anti-tail. This was a previous “Comet of the Week” and the details of its appearance are discussed in that Presentation.

But 1957 wasn’t over as far as bright comets were concerned, for another one appeared just a few months later. Unlike Comet Arend-Roland, however, which was discovered several months in advance thus creating widespread anticipation of its appearance, this second visitor approached the inner solar system from the deep south and then spent the last several weeks prior to perihelion passage hidden in sunlight on the far side of the sun from Earth. When it burst into view around the beginning of August it was already bright and fully developed.

The first person to report seeing the comet was a Japanese observer, Sukehiro Kuragano, who saw it on the morning of July 29, but unfortunately, his report was delayed for two weeks. An American Airlines pilot, Peter Cherbak, saw the comet while flying over Nebraska on July 31, and after confirming his sighting the following morning notified Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles, but this report, too, was delayed. Numerous independent discoveries followed over the next few mornings, including one by a 15-year-old British amateur astronomer, Clive Hare, who saw the comet on August 3. Meanwhile, on the morning of August 2, Antonin Mrkos, who was part of the visual comet-hunting program being conducted at Skalnate Pleso Observatory in then-Czechoslovakia (present-day Slovakia), was measuring the morning skyglow at the observatory on Lomnicky Stit when he noticed a comet’s tail extending from below the horizon, and shortly thereafter he saw the comet’s head rising. Having discovered nine previous comets he knew exactly what to do and notified the IAU’s Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (then located at Copenhagen Observatory), which very quickly announced the discovery as “Comet Mrkos.” Even after the other, and earlier, discoveries became known the IAU decided to leave the name unchanged in order to prevent confusion. (Nowadays the IAU’s practice is to wait to assign names to newly-discovered comets in the case earlier discoveries might come to light, so if this type of scenario were to happen again the final naming would more accurately reflect the actual precedence of discoveries.)

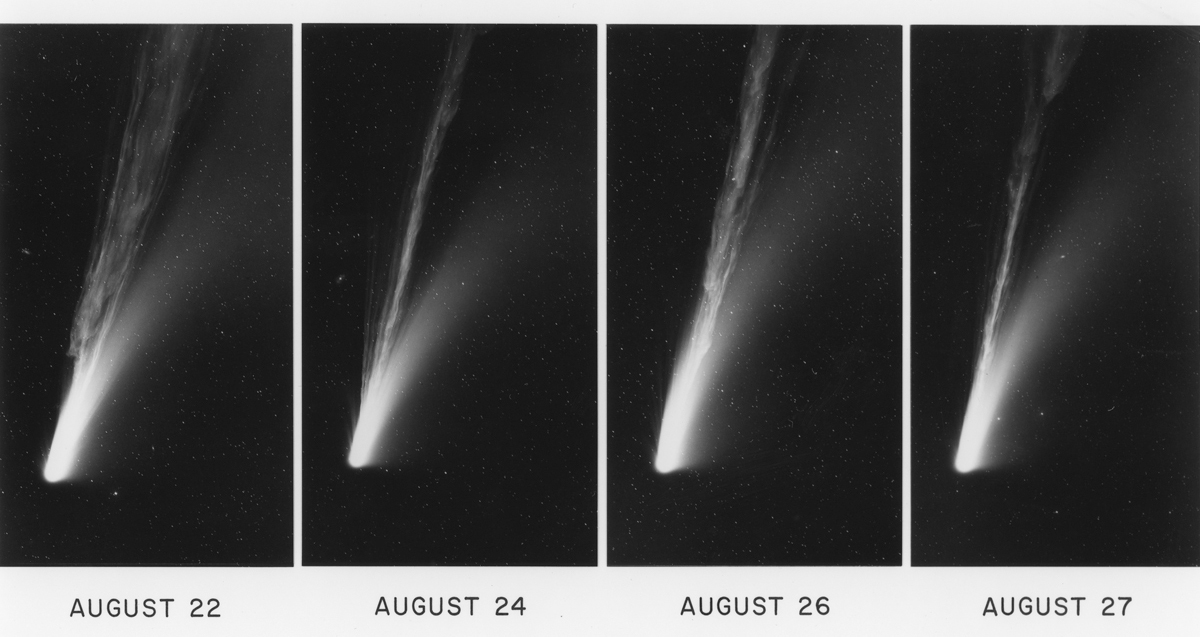

Comet Mrkos was initially a morning-sky object located well north of the sun, and it moved eastward, being directly north of the sun on August 5 and thereafter becoming primarily visible in the evening sky after dusk. By an interesting coincidence, during the second week of August, it was located in the same position relative to the horizon that Comet Arend-Roland had occupied less than four months earlier. Its brightness was reported as being as high as 1st magnitude in early August, and it faded fairly slowly thereafter, still being around 3rd magnitude during the latter part of that month. In addition to a prominent ion tail that reached a maximum length of about 10 degrees, the comet also displayed a bright and prominent curved dust tail, initially around 5 degrees long in early August but increasing to 15 degrees around mid-month. This tail featured several of what are called “synchronic bands,” which have been observed in a handful of other bright dusty comets; the mechanisms that produce these and other features in cometary tails are the subjects of a future “Special Topics” presentation. The recent Comet NEOWISE C/2020 F3 exhibited a relatively similar overall appearance, although Comet Mrkos was apparently slightly brighter.

Although still as bright as 4th magnitude in early September, Comet Mrkos faded more rapidly that month, dropping below naked-eye visibility towards the end of that month and fading further to 7th magnitude when it disappeared into evening twilight during October. Following conjunction with the sun, it was recovered as a faint object in the morning sky in February 1958 and thereafter followed until July. According to orbital calculations, it should return in approximately 6000 years.

More from Week 33:

This Week in History Special Topic Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page