We’ve all seen or played in one of those inflatable bounce houses at a carnival or a friend’s birthday party. Now just imagine a bounce house that you can live inside of in outer space.

While much more advanced than a bounce house, that’s what Bigelow Aerospace is pursuing. They are designing and building inflatable habitats that can be used in outer space, providing work and living areas while protecting the occupants from the harsh environment of space.

When you look at the International Space Station modules, they are hard shelled, looking very sturdy and strong, so the idea of something that inflates to become a module that humans can inhabit seems very farfetched, but not to Bigelow Aerospace founder Robert Bigelow.

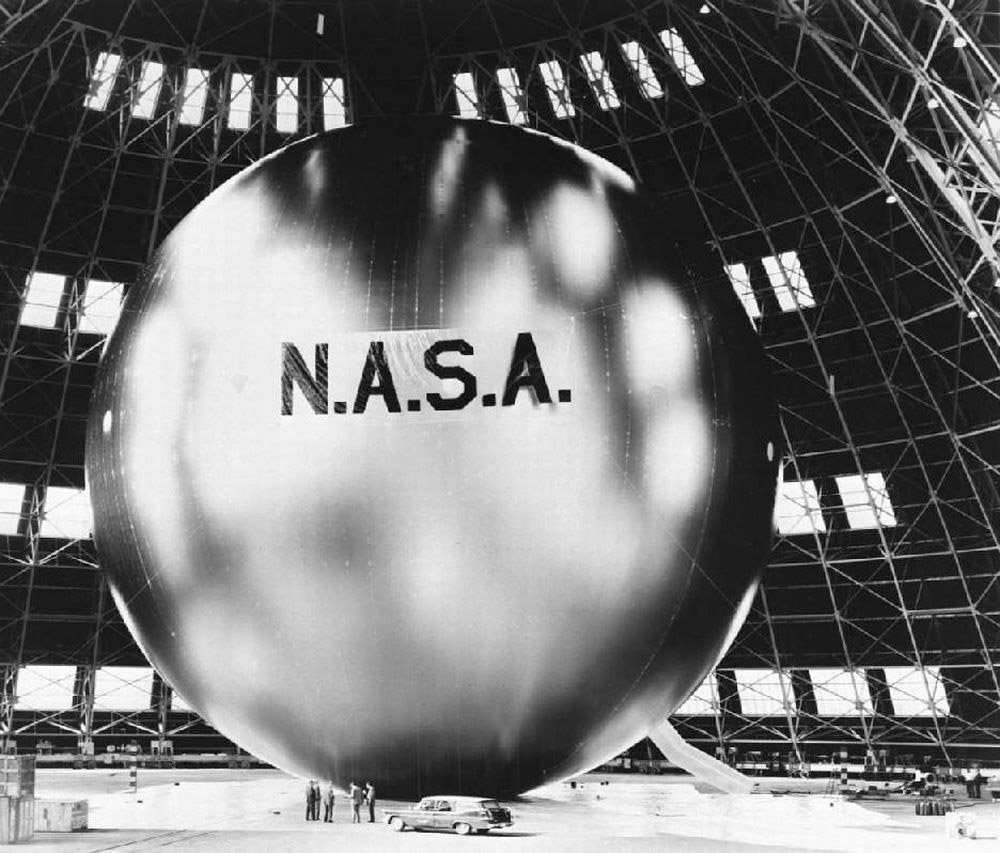

The idea of inflatable spacecraft is not exactly new. In 1958, the newly formed National Aeronautics and Space Administration, NASA, first started a project to design and build such a spacecraft.

The Echo-1 satellite was launched on August 12, 1960 aboard a Thor-Delta Launch vehicle inside a launch canister that was only 3 feet in diameter. The satellite’s skin was comprised of 31,416 square feet of Mylar, which was only 0.0127 mm thick. To put that into perspective, a human hair is approximately 0.06 to 0.10 mm thick. The Mylar was covered with a thin aluminum coating that allowed signals to bounce off the satellite when sent to it. When inflated on orbit, it had a diameter of over 100 feet, higher than a 10 story building.

It deployed at 1,000 miles high and was easily seen with the naked eye here on Earth. It lasted 8 years in orbit before finally reentering the atmosphere and burning up.

While Echo-1 was a long way from being a spacecraft that humans could inhabit, it was basically a large balloon with no life support systems, no radiation protection, no facilities to work or sleep in, but it proved that inflatable spacecraft were indeed feasible.

Inflatable spacecraft were not looked into again until 1992 when NASA was tasked with developing a plan for a manned mission to Mars. Unfortunately the Mars Mission planning was cancelled and once again, inflatable habitats were also.

In 1997 when planning was well underway for the International Space Station (ISS), the idea was revived as a possibility for use on the ISS. NASA had designed and built a test Transhab module before the inflatable habitat initiative was cancelled in 2000.

Robert Bigelow heard of the latest cancellation of the inflatable habitats by NASA and persuaded NASA to grant him exclusive licensing to the technology and formed Bigelow Aerospace. The company is based in the desert area of North Las Vegas, an area that most people would not think of when they think of spacecraft development.

Despite having the technology licensed from NASA, the company had to re-develop a lot of the current technologies before they could launch a test habitat. The end result, in only five years, was the launch of the Genesis I test habitat on July 12. 2006. Genesis I is still in service today providing important test data back to mission flight controllers at Bigelow’s Las Vegas facility.

Another test article, Genesis II, launched just one year later, and is also still operational. Both spacecraft have six inch multi-layer skins and measure 14.43 feet long by 8.33 ft. in diameter which results in 11.5 cubic meters of useable volume inside. Before being expanded, the diameter of the spacecraft is just 4.24 feet in diameter which saves a lot of volume in the launch vehicle payload faring.

The vehicles orbit the earth every 96 minutes, 350 miles up, travelling at nearly 17,000 MPH. You can track Genesis I at www.satview.org/?sat_id=29252U and Genesis II at www.satview.org/?sat_id=31789U.

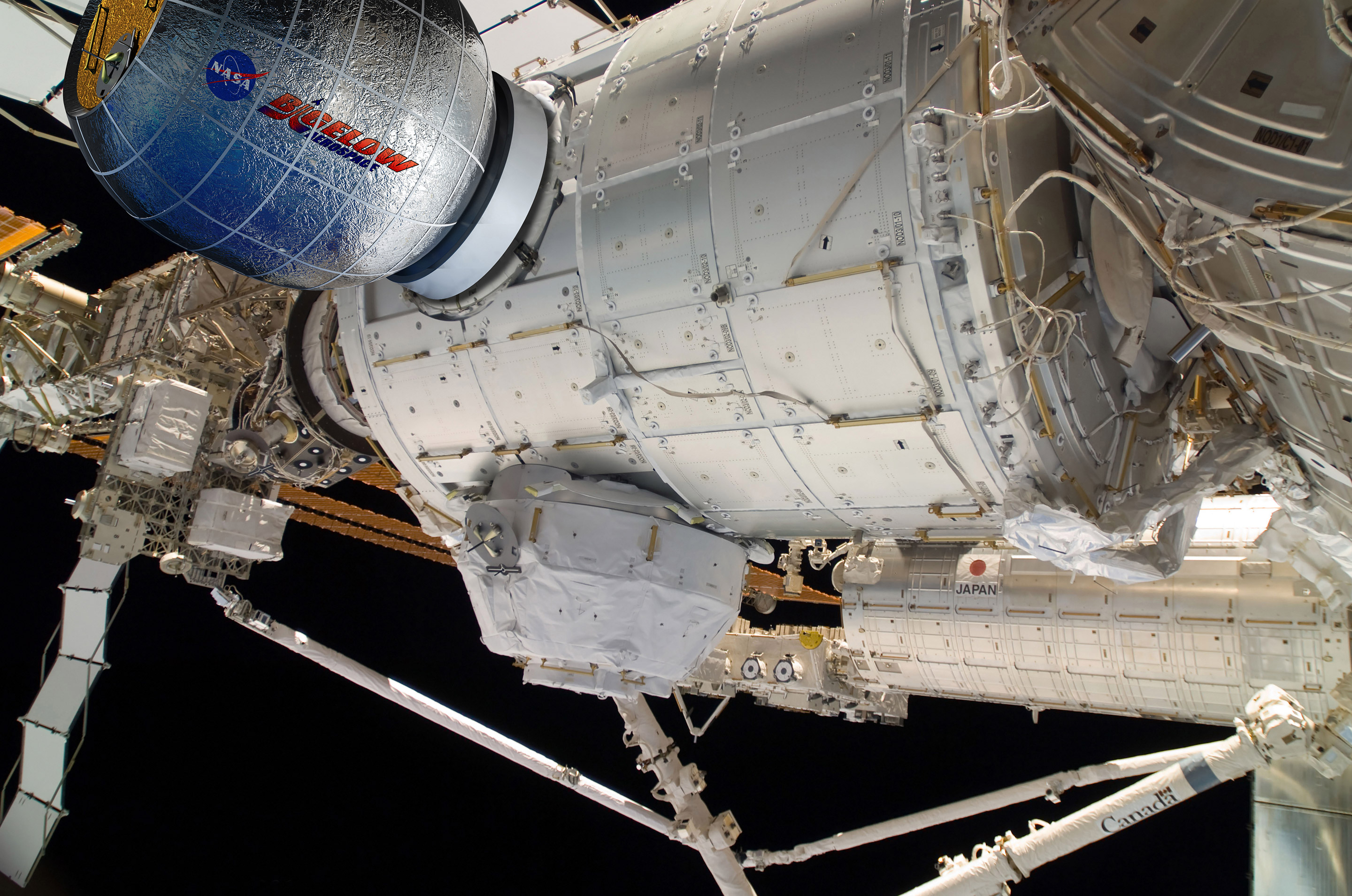

On January 16, 2013, with the Genesis test articles continuing to prove the technology and reliability of Bigelow’s designs, NASA awarded a $17.8 million contract to Bigelow Aerospace to provide a Bigelow Expandable Activity Module (BEAM) for a two-year technology demonstration.

BEAM is scheduled to launch aboard a Falcon 9 rocket in the unpressurized cargo area (referred to as the trunk) of the Dragon capsule. Upon arrival at the ISS, the crew will remove the BEAM habitat from the Dragon’s trunk and dock it to the aft port of Node 3. After successful docking the crew will initiate the deployment sequence and Beam will expand to 13 feet long by 10.5 feet in diameter. Once fully deployed, one of the crew will enter the BEAM, becoming the first astronaut to enter an inflatable habitat.

During the two-year test period, ISS crew members, Mission Controllers on the ground, and instruments embedded in the module will monitor BEAM’s performance. Data recorded will include its structural integrity and leak rate, radiation levels, and temperature changes compared with traditional aluminum modules.

Due to the lack of a metal skin, the Bigelow habitats should actually provide better radiation shielding than the ISS modules currently in use.

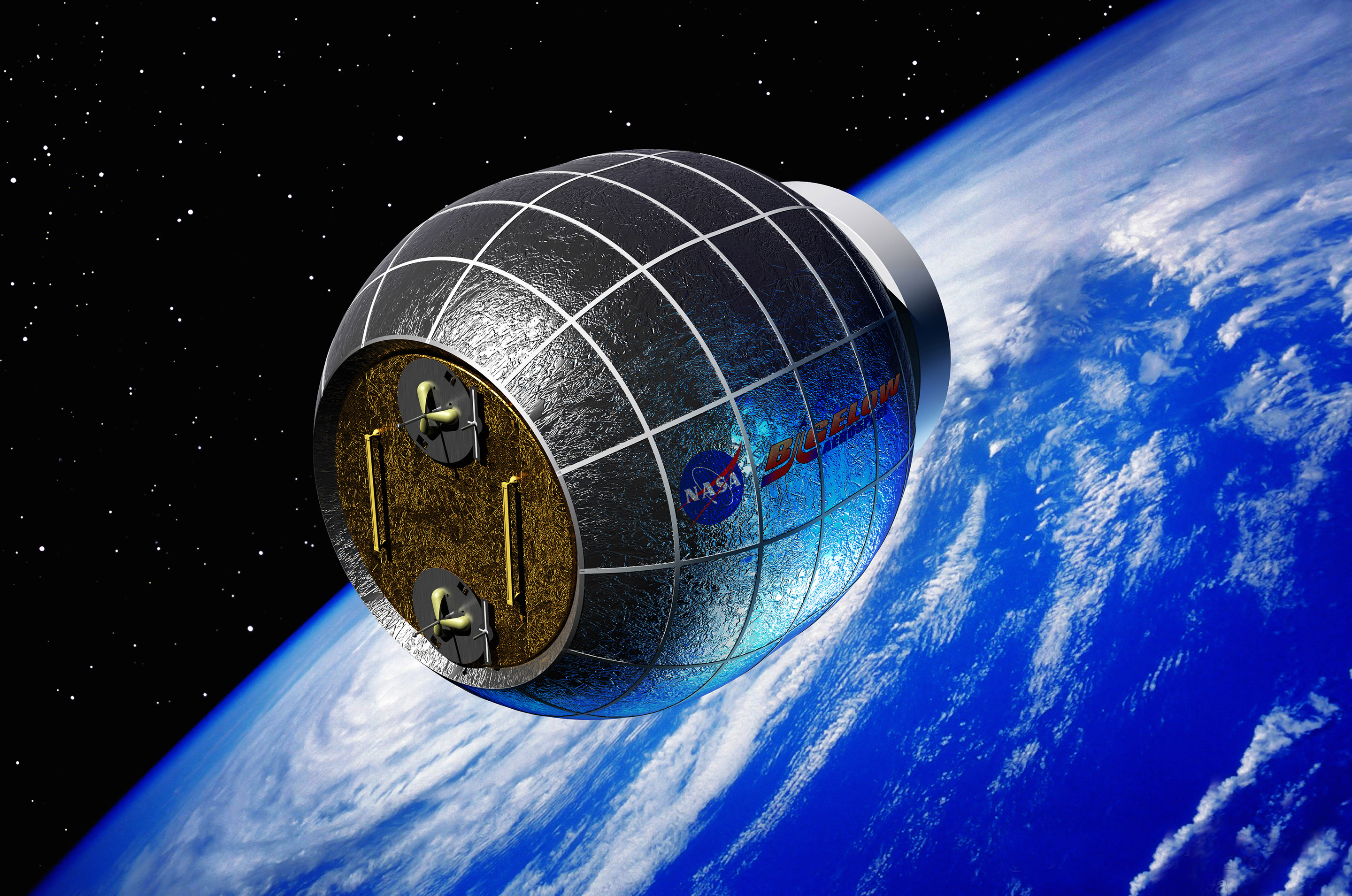

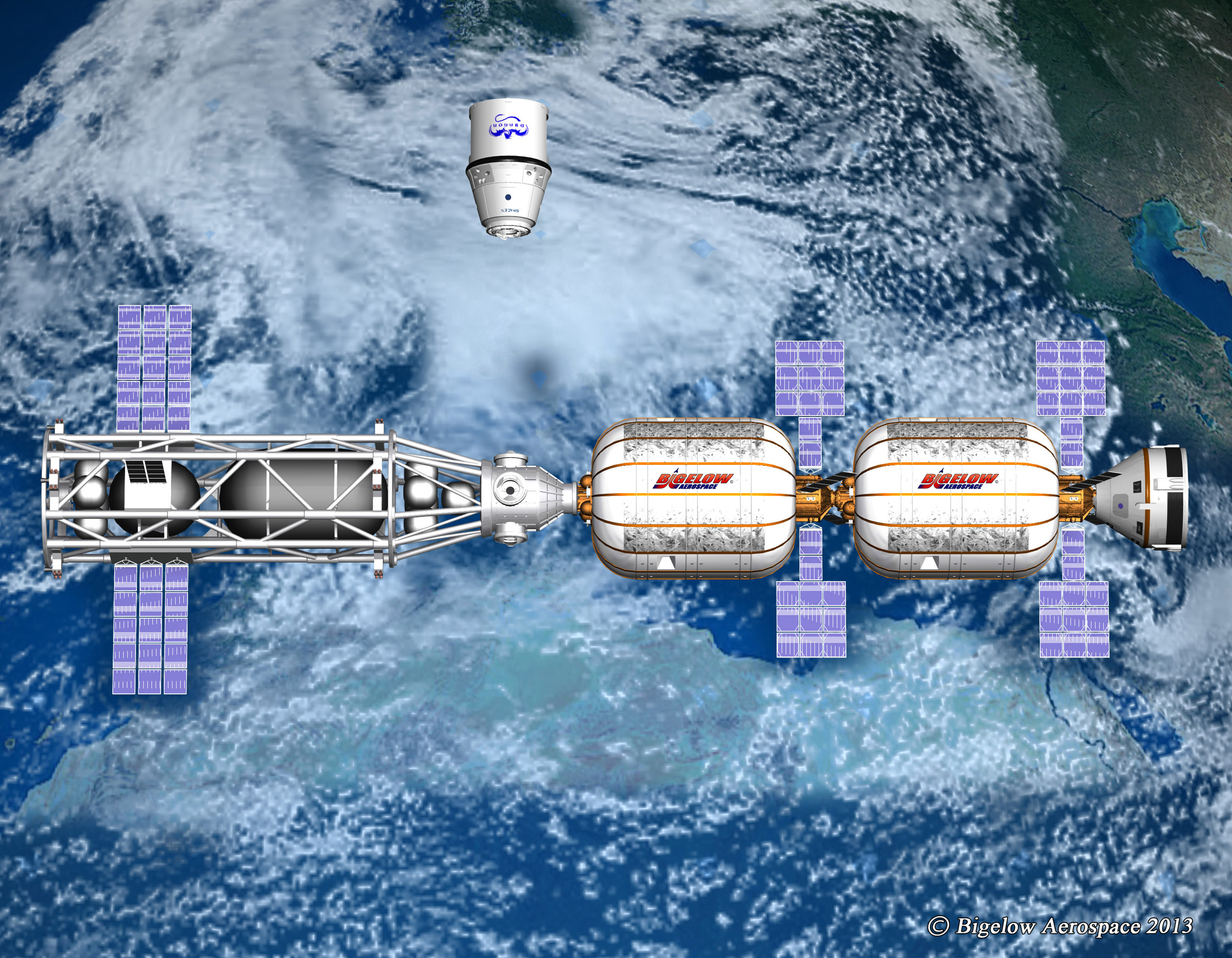

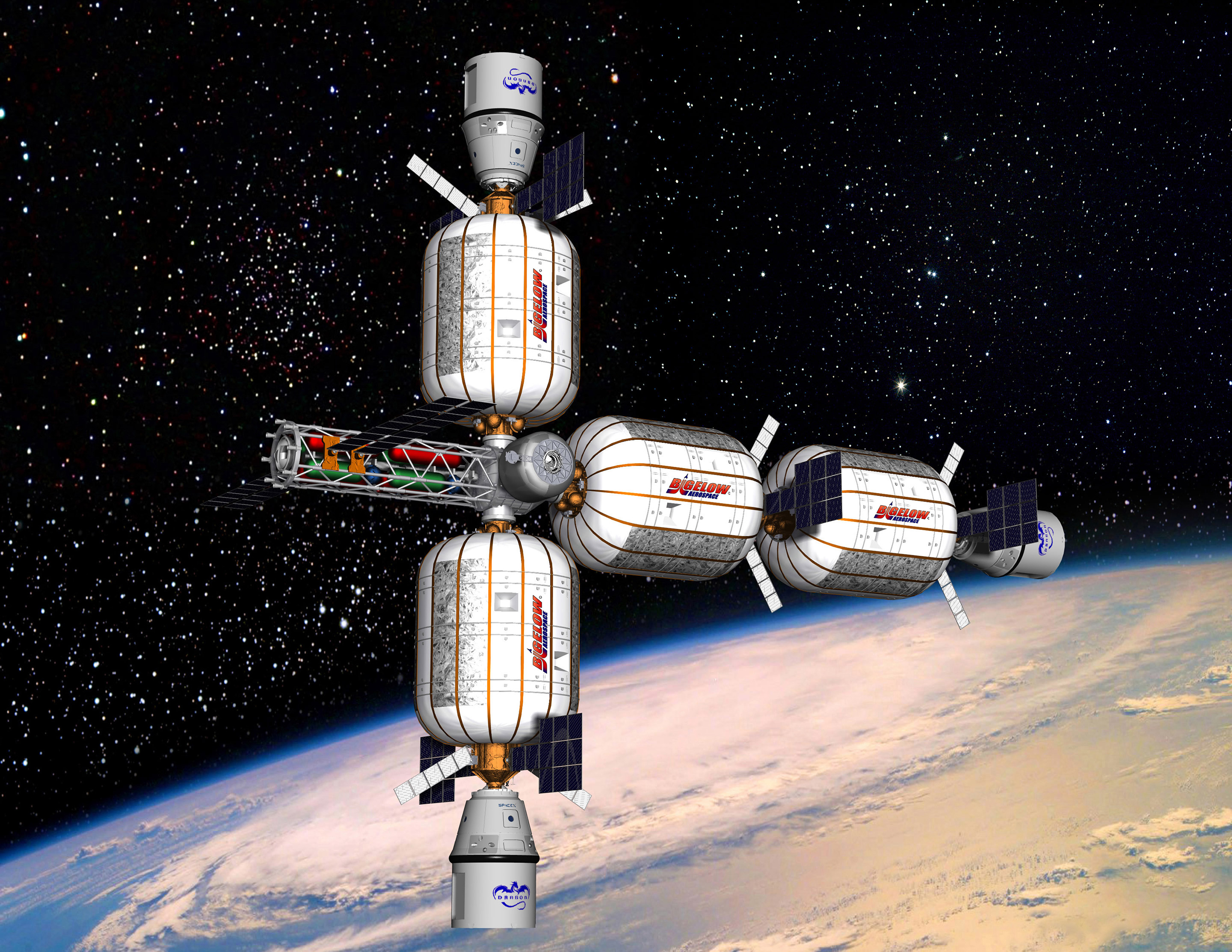

Following BEAM will be the BA 330 modules. These are massive habitats at 45 feet in length and over 22 feet in diameter. They will provide 330 cubic meters (almost 11,760 cubic feet) of useable interior space. To put that into perspective, a 12 ft. by 12 ft. bedroom with 8 foot high ceilings is only 1,152 cubic feet of space. The Harmony module on the ISS provides just 2,666 cubic feet of living space.

One BA 330 will be able to support a crew of 6 and the modules can be connected to form a larger complex. The BA 330 has an innovative Micrometeorite and Orbital Debris Shield, which in testing by Bigelow has proven superior to the Aluminum skinned modules currently in use on the ISS. Each BA 330 will have two propulsion systems for maneuvers and orbital boosts and independent avionics systems to support those maneuvers. Electrical power will be supplied by solar arrays and storage batteries. Each BA 300 will have its own Environment Control and Life Support System including lavatory and hygiene facilities. And for a room with a view, the BA 330 sports 4 large windows which are UV coated for protection.

The uses for such a large habitat range from a space station, to a hydroponics farm growing some of the food for the crew, to medical research, even a storage facility where crews venturing out into deep space could dock and resupply before starting, or during their voyage.

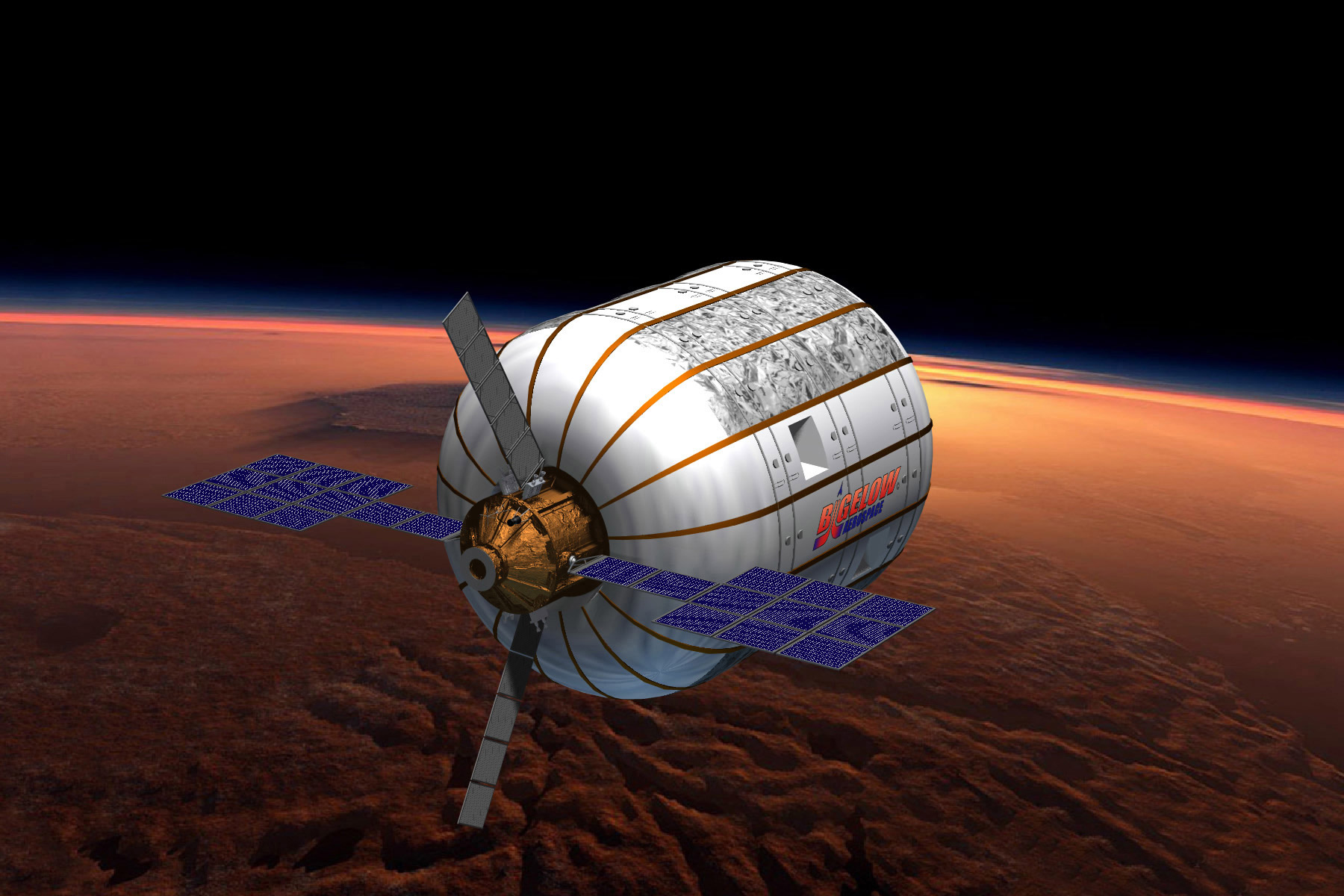

Other models of the BA 330 are being developed also. The BA 330-DS is modified to be used in deep space, such as in lunar orbit or in one of the Lagrange Points, where gravitational forces act on a spacecraft in such a way to allow it to orbit with the celestial body they are near. This effectively neutralizes the movement of the spacecraft, allowing it to reside in the same point indefinitely. The main difference between the Deep Space and regular BA 330 is additional radiation shielding.

Another version known as the BA 330-MDS is configured to allow landing on another celestial body, such as the Moon. It would come with propulsion systems which would allow it to land on the surface and modifications to the structure to allow it to reside on the surface. With its large size, the BA 330-MDs would essentially be its own Lunar Base once landed on the surface of the Moon.

Robert Bigelow is not stopping there either. Bigelow Aerospace is designing an even larger habitat named Olympus. Due to its massive interior volume of 2,250 cubic meters (79,458 cubic feet) , it would need to be launched on NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS), or perhaps the SpaceX Falcon 9 Heavy which is also in the design and construction phase.

Similar in design to the BA 330 but on a much larger scale, it could accommodate a crew of 24 or more. A modified version of this massive habitat could allow smaller spacecraft to enter it for transport, or so that astronauts could work on them, essentially a hangar in space. Due to the massive size, the Olympus habitats would not be built in Las Vegas. They would need to be built on a waterway, most likely close to the launch facility where they would launch from.

Also in the planning stages is an effort to launch their own astronauts or perhaps even paid tourists into space. But unlike all other U.S. manned launches coming from Cape Kennedy / Cape Canveral, Bigelow is looking at the recently expanded launch site at Wallops Island, Virginia. Recently, Director of D.C. Operations Mike Gold expressed interest in that facility as it would have less traffic then the Florida facilities allowing more flexibility and frequency of launches. A proposal to NASA will hopefully be submitted soon.

The future of space exploration seems to indeed include expandable modules, and Bigelow Aerospace is leading the way. NASA is very interested in them once again, and Robert Bigelow is so sure of their success that he has invested over a quarter of a billion dollars into this venture already. Maybe someday you will be able to catch a ride aboard a Dragon or Dream Chaser spacecraft and head to one of his habitats in outer space. But for now, just think about the amazing future that lies ahead the next time you see one of those bounce houses.

Information sources:

- www.delmarvanow.com/story/news/2014/02/17/manned-missions-from-wallops/5551307/

- www.bigelowaerospace.com/index.php

- www.nasaspaceflight.com/2014/02/affordable-habitats-more-buck-rogers-less-money-bigelow/