The following article is an account of several meetings, chats and short interviews I have had with the first Briton in space, Helen P. Sharman

I first met Helen over 15 years ago at the University of Sheffield when I attended a lecture organised by the University of Sheffield’s Chemistry Society at which she told an enthusiastic audience about her “Journey Into Space” on the Juno mission with the Russian Soviet Union. I have since met Helen several times.

At our initial meeting her lecture began with an introduction from a former member of the current university Chemistry Society who reminded us that the University of Sheffield was where Helen had taken a degree in chemistry a few years ago (I had done my degree in the building next to hers), he then continued his introduction by embarrassing Helen with production of her 3rd year dissertation project which he offered to anyone willing to buy him a pint of beer.

Helen introduced her talk by stating that being a cosmonaut was as she put it “just a job” (What a job to have, I thought!). After leaving University Helen went on to work in industry and began her working career with GEC but then moved in a different direction by taking a job with Mars confectionery in their ice cream department, a fact that did not go unnoticed by the media who readily printed headlines such as “Girl from Mars blasts off to the stars” and “Mars girl blasts off for the galaxy” after her selection for the mission into space, much to Helen’s amusement.

I also wanted to know why the mission had been named JUNO as book and online accounts don’t seem to explain so I asked Helen, “It was a clever marketing associate who came up with the name. In ancient Rome, Juno was the goddess who watched over women and marriage. My Flight was seen as a marriage of East and West like the Apollo Soyuz Mission so the name stuck.”

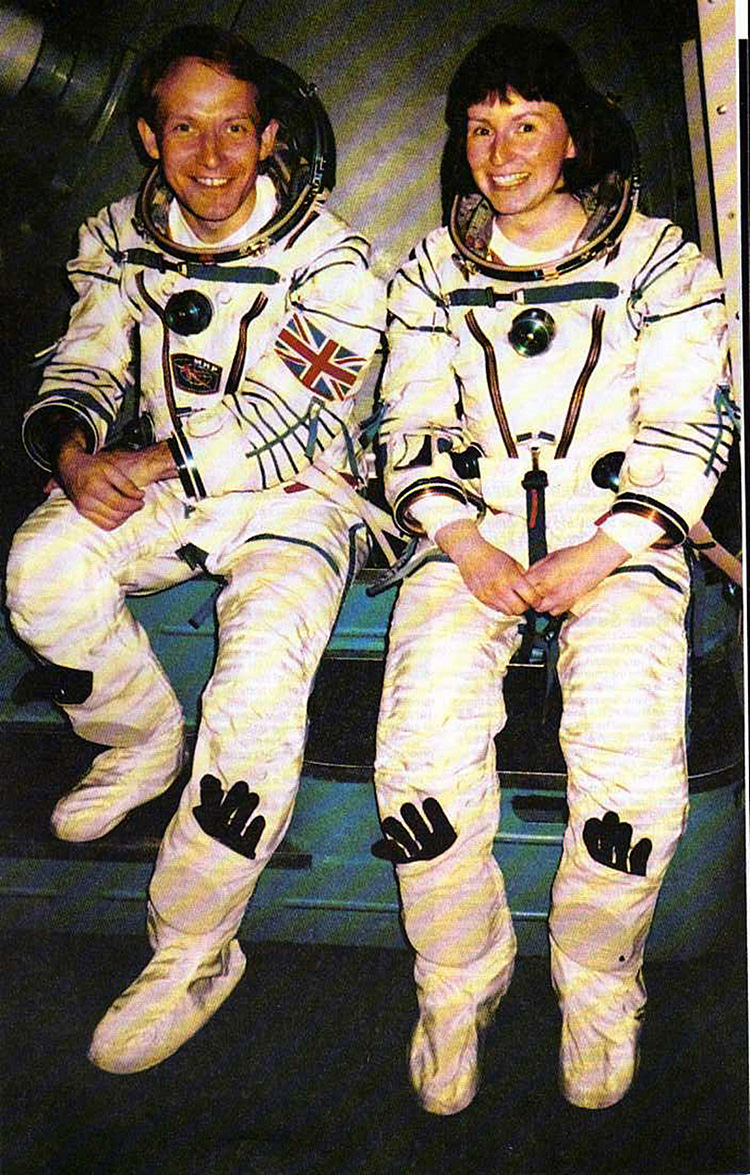

Why become an astronaut/cosmonaut?. This was a question that she would ask herself many times in the months to come, but it was an unusual way by which she actually did become our first space traveller. Whilst driving home one evening from work Helen had been flicking through the radio stations in the car when she heard an advert that made her really listen. “Astronaut wanted no experience necessary”. Helen made a mental note and later sent in the application form (As did many thousands of others) yet after many interviews, psychological analysis and medical examinations, Helen was selected along with Timothy Mace from the Army Air Corps as the two candidates for the mission. Both were then given only 4 days notice to resign their jobs, sell their cars and head for Star City, a military and cosmonaut training facility of 4-5 thousand people just 1 hour’s drive from Moscow.

When the media had initially realised that a Briton was going into space enthusiasm grew, after all it was something new and exiting, yet when the pair met the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher her response was typical “We the British don’t do that sort of thing” so no government funding was forthcoming. The entire mission would have to rely on corporate sponsorship if it was to be a success. (This attitude does not seem to have altered in my view, even the Union Jack no longer flies on Europe’s most successful launcher Ariane).

After the shock of arriving in an establishment where no one spoke any English, Helen and Timothy’s ability to learn foreign languages quickly (A fact that played a part in their initial selection) came to the fore. Helens personal instructor could not speak a word of English at all and one of the pairs lecturers had even started a class by saying “Bon jour, J’mapelle” (my name is) in French as he had trained the crew before Helens, that just happened to have a French crew member. The routine was by now familiar, each day dawned early and was set out methodically. Two hour’s of lectures on mathematics and lectures on astronomy (carried out in a planetarium) were followed by a short interlude and then more studies every day for almost 18 months.

Helen explained that the Russian instructors thought that the Russians were better than the Americans and that Russian cosmonauts were also far superior to their American counterparts, as they had to do “99 exams”, both Helen and Timothy thought that this was a joke, that is until exam time came round, and they realised how serious the instructors had actually been.

Throughout the lecture Helen had an underlying philosophy “Keep your eyes on the end goal and keep going until you get there” which no matter what you do in life or work seems like pretty sound advice. And it certainly worked in this case.

The training proper for the mission began in the Soviet version of the American KC-135 which is the aircraft that flies huge parabolic curves in order to simulate a weightless environment (A lot of Apollo 13 The movie was filmed in the NASA aircraft), something that Helen really enjoyed, Helen resumed “The Russians believe the best people to fly in space are women, although leg-less ones would be better (Just like being in the Union bar on a Friday night I thought) but in all seriousness she explained that legs are really useless in space anyway and that it was a real possibility that we could see a disabled person fly on a space mission some time in the near future.

What do the Soviets call their equivalent “Vomit Comet” I asked?

“The Russians do not actually have a name for this particular aircraft. The difference between the Russian and American version lies in the fact that the Russian aircraft is a modified cargo plane, and when flying the parabolic curve it does not afford as much time weightless as the US version. There is also another problem because when manoeuvres such as this are being carried out, not only are the crew floating but all the aircraft’s oil and hydraulic fluid are experiencing the same effect so we had to return to base regularly to have the plane serviced and for safety checks every time we used it”.

Helen recalled how the Russians are very good at planning for all eventualities, for example. Although on returning to earth the mission was supposed to land on solid ground her training taught her how to survive in the sea for 3 days (A real possibility if a forced re-entry occurred) and there were times when she thought, how will this technology get us into and out of space?, there were also many times when Helen and Timothy thought of giving up and quitting the program. Although the technology is “Poor” and mission control resembles a shed with Christmas lights on, it was trust that played a key role in not only Helens particular mission but also each and every mission past, present and future. However even more training was required and Helen spent many hours strapped into a gyroscope being turned round and round upside down all in an attempt to confuse her vestibular system in the inner ear (organs that aid balance and that are sensitive to movement and acceleration) into making her sick. Helen though never once vomited and she never did suffer from any sort of motion sickness at any stage of her training or during the mission proper.

Eventually selection time arrived and after the 99 exams Helen was chosen in preference to Timothy as prime crewmembers for the mission. Her role was to be that of a mission specialist in charge of experiments, and once the reality of being Britain’s first citizen in space had sunk in she went on to meet the other two members of her crew along with their families in an attempt to bring them closer together so they could tell what each was likely to do.

Back in Star City more mundane chores had to be done, Helen had to be fitted for her space suit. “It’s the best made to measure outfit that I’ve ever had” she enthused but then it’s hardly surprising seeing as she was measured in 72 different places before the suit was made. Once in the suit Helen explained how difficult it was to stand upright because the shoulders and the sides of the suit have wire in them for support and durability, “When you see them (the cosmonauts) on their way to the launch pad the look hunched up, this is not because they have had too much vodka to drink or that they are tired due to lack of sleep, it’s just that the wire makes movement so difficult”.

The seat in which Helen and all cosmonauts sit is also made to measure but at the base there is a gap of about 4-5 cm where ones back fits. Helen continued, “Because your spine stretches in the weightless environment this little gap is essential to allow for the 2cm or more stretch that the spine will experience, I liked that, it made me feel taller for a time”.

When the time for the launch approached Helen couldn’t help herself thinking back to her education and certain laws that she had encountered. The one which came to mind was one of the Newtonian laws of motion, “every action has an equal and opposite reaction”, this would be so true once the rocket she was to fly on had lifted of from the Baikonur Cosmodrome at Tyuratam near Vladivostok in eastern Russia.The thrust being ejected from the rocket so powerful that it overcomes any problem of gravity.

“The launch is exiting not having done one before but it’s also rather mundane” Helen recounted, the reason being that the crew are strapped into their seats many hours before the launch itself, “It’s not scary” she told the by now enthralled, captive audience “As there is no unknown, you feel really prepared”. At launch the acceleration builds, drops then builds yet again as the various stages of the rocket are used up and after approximately 8 minutes a bang is heard and orbit is attained.

I took the time to ask Helen about the launch phase of the mission and her on orbit rendezvous with Mir were there any problems?

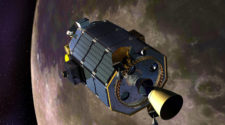

“The mission I took part in had its problems too; we had an O2 leak during the launch which had to be sorted out quickly in the spacecraft as we lifted off. The automated docking had to be aborted and a manual docking carried out and we had minor problems with other equipment also. That is what space flight is like, and your training prepares you for all the possible malfunctions that may take place. You are aware that you could be killed at any time, I’m catching the train back down to London this evening and something could happen on that, it’s something you try to put out of your mind”.

Although Helen was still strapped tightly into her seat, she could no longer feel her back on it but felt as if the straps that were holding her in place, were, somehow, doing their job a little more efficiently. During the launch Helen had also lost some 2 litres of sweat and was ready to have a drink, and with so little space inside a Soyuz-T space craft they had to take it in turns. During the first few hours in orbit the crew had to change into their flight suits which are in fact specially designed so that they produce no dust what so ever, important as any dust could impair respiratory functions or even damage the space craft itself.

During the two days before the docking with Mir was completed, the crew’s bodies underwent many changes, changes induced by their new environment; “The eyes have trouble focusing on distant objects for a while” we were told. Another problem encountered during space travel is the chemical imbalance of the body’s hormone system, which results in the kidney’s compensating by loosing urine to try and restore the balance. Gravity, something that Helens University lecturers had told her never played a part in anything other than on earth, still has an effect whilst a space craft is in orbit. As the space craft orbits, it is in fact in a state of perpetual free fall as gravity pulls it around the globe, Mir itself has to have its orbit boosted every few months in order to stop it crashing back down to earth. Helen told of how she had discussed this with astronomers and physicists alike and that they had all come to the same conclusion that, no matter where you are in the universe, gravity will still play a role whether it be in earth orbit or around some far distant galaxy so you are probably never really weightless at all.

The docking with Mir was something of a problem as the usual automated docking system failed and a manual docking had to be carried out. After two days of chasing Mir they had finally hard docked and transfer could begin. Helen was allowed in first and was greeted by the two crew members who were already aboard the station, crew members that would after 6 more days return to earth in the same capsule as Helen. The first impression Helen had of Mir was how big it actually was (Mir was two modules smaller whilst Helen was aboard, than when Mike Foale had his well-documented problems a few years later) and was relieved that she could finally have a good stretch. “Every day is a bad hair day in space” she told everyone, this was shown graphically with a slide of Helen floating around with her hair resembling some out of control seventies Afro from a Startsky and Hutch programme.

As already mentioned, Helen was to carry out various experiments in her role as mission specialist and these included observations on germinating potato seeds, and another in which plant seeds germinated surrounded by magnets. Others included earth observation, growing large protein crystals which can’t be done on earth and her favourite where ceramic oxides are placed on photographic film which are then exposed to the vacuum of space. This apparently leads to the production of super conductors. Helen believes that the future of space flight lies in orbiting factories where new materials can be produced and utilised for the space industry. Metals can be mixed in space whereas on earth they cannot, leading to the manufacture of super alloys. On her trip there was time for play though and on the station were items of amusement such as a guitar and keyboard (The idea of spending 6 months listening to someone who cant play either doesn’t seem too appealing though) and a cassette player for real music, but the most used things aboard the station are obviously the windows, where the earth can be viewed passing by.

In the Mir station the air is filtered through lithium chlorate canisters which replenish the oxygen but just as important is the fan that circulates it. This is essential because there are no convection currents in space, therefore without a fan the air would not move and a cosmonaut or astronaut could quite easily suffocate on their own expelled carbon dioxide. When any item goes missing on Mir Helen suggested the most likely place to find it would be the air intakes that are dotted around the station, a slide illustrated this as we could clearly see a film canister, hair brush and even a tooth brush stuck up against one.

When any cargo is sent up into space, the materials they are made from have to be checked very carefully. A problem encountered in the past on Mir was the out gassing caused by certain plastics. On earth this is not a problem as the atmosphere carries any toxins away but on a space station this could have serious consequences. One item that also caused a stir was the Mir weighing scales, stupid idea I hear you say but these scales measure mass not weight by means of a bouncing spring that moves when it is sat on.

One of the original crew that had been aboard for 6 months was using a piece of apparatus that was designed to draw blood back into his legs in preparation for his now near return to gravity on earth, anyone who has seen Wallace and Gromit in the Wrong Trousers and can recall the trousers Wallace ended up wearing, will have a good idea as to what the ones on Mir look like, though they did suit Wallace much better. This particular member of the Mir crew also, as Helen found out, had an affinity for oranges and after 6 months without even seeing one, you would feel if he did find one that he would eat it straight away but when he was presented with one that Helen’s crew had smuggled in, he was so pleased to see it he actually played with it for 2 days before he could actually bring himself to eat it at all.

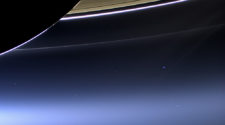

The toilet is something that everyone wants to know about and the one aboard Mir is essentially the same design as that on the shuttle but the one on Mir can recycle more waste and any urine can be converted back into drinking water in an emergency situation, something the audience did not seem too keen on. The sleeping arrangements are by way of a bunk system and as Helen said “It’s basic but sleeping in space is the most natural way to have a rest and be comfortable”. She was even lucky enough to have her own window complete with meteoroid impact chip caused by an errant meteor the week before. Each 24 hour period resulted in 16 orbits of the earth each with associated sunrise and sunset. Helen, although disappointed with how brown the land surface of the earth was from space was amazed at the clouds and how blue the oceans were, in fact she commented “It’s a blue I’ve never seen before or since” and no doubt that anyone who has flown in space could tell exactly the same story. “The sunrise was magnificent, and you could clearly see the curvature of the earth form 100Km up”.

Was it always the plan that you would only fly one mission I asked, and if so why?.

“Yes, because this was a commercial mission, it was, from the outset a one off. Money and support meant that it could not be anything else. Our own government were not interested in funding us and only the money raised by our industrial sponsors, could have financed such a trip, so in response to your question it was only ever going to be a one off mission”.

Soon Helen began to explain how only after 8 days you do begin to miss your family and friends and told of how she felt for her colleagues who had been up there for 6 month’s already. Studies have actually shown that the optimum time to spend in space is 3 months and it is important that the right type of person is chosen for long duration missions such as those that may one day take us to Mars.

By now though the mission was complete and preparations were underway for a hand over of the station to the two crew members with whom Helen had arrived and the return of Helen and the departing crew.

During the launch phase of the mission Helen had experienced 3.5 G or 3.5 times the gravity of earth but on re-entry she would experience 4.5 G. The re-entry fortunately, went as planned and although they drifted just off the landing zone, they nevertheless made a flawless landing in northern Kazakhstan. When the rescue team arrived, the capsule was rolled over and the hatch opened up. The inrush of air felt good and once the crew had been hauled out of the craft Helen was in for another surprise. The crewman who had just spent 6 months in orbit just stood up and walked around as if he had never been in space at all something Helen commented on as “Being hard to believe”.

The mission was finally over and Helen’s closing comments were “Well, that’s that. It was a job and I was lucky enough to do it, I was just in the right place at the right time”

I finished our latest meeting by asking Helen if she though ISS was viable.

“Certainly, but only with the joint co-operation of other countries and their involvement with the International Space Station project. Mir was an important space platform ISS even more so, I only hope that the certain partners don’t try to take everything over. Space is for the benefit of us all not just a select few”.

Today, Helen is somewhat of a reclusive person, preferring privacy to a life of the thrust of fame which it has to be said her choice. She is, and always will be the first Briton in space, and she is from my home city, so I have more than one reason to be proud of her.