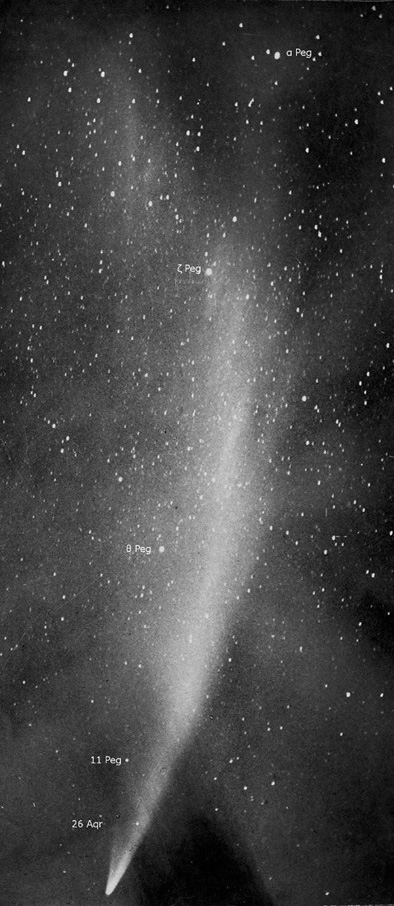

Perihelion: 1910 January 17.59, q = 0.129 AU

In early 1910 the entire world – astronomers and lay public alike – awaited the imminent return of Comet 1P/Halley, which had been recovered the previous September and which was already detectable with moderate-sized telescopes. While Halley would go on to put on a spectacular display around the time of its perihelion passage in April, it was upstaged early in the year by this brilliant comet which approached Earth from the far side of the sun. It didn’t receive the names of any discoverers but instead is usually referred to as the “Daylight Comet of 1910” or as the “Great January Comet;” its formal designations are 1910a and 1910 I (old style) and C/1910 A1 (new style).

The comet was apparently first spotted on the morning of January 12 by miners at the Transvaal Premier Diamond Mine in South Africa, who spotted it in bright twilight as an object of magnitude -1 and with a distinct tail. Other workers spotted it on subsequent mornings, and after receiving word from the editor of a local newspaper Robert Innes, the Director of the Transvaal Observatory, successfully observed it on the morning of the 17th.

From the 17th through the 19th the comet was widely observed some 3 ½ degrees from the sun as a brilliant object of magnitude -4 to -5 and plainly visible to the unaided eye during broad daylight. By the evening of the 20th it was starting to become visible in evening twilight from the northern hemisphere, and was described as being “as bright as Venus” with a tail some ten degrees long (although both twilight and light from the full moon may have shortened the visible tail length). As the comet climbed higher in the evening sky on subsequent nights (and as the moon cleared out from the evening sky) it began fading, but at the same time the visible tail length increased dramatically, to as long as 45 to 50 degrees by late January and the beginning of February. This tail exhibited a distinct curvature near its end – being “shaped like a curved horn” according to some accounts – and this was apparently due to “synchronic bands” which in turn indicated a large presence of dust in the comet. Spectra of the comet, including some obtained in daylight when it was near perihelion, also indicated a high dust content.

The comet had faded to 1st or 2nd magnitude by late January and to 3rd magnitude by early February. It was never far from the sun, being at a maximum elongation of 22 degrees at the end of the first week of February, and by the middle of that month had dropped below naked-eye visibility. After being in conjunction with the sun late that month it emerged into the morning sky in early March near 8th magnitude and faded steadily from that point, with the final observations being obtained in mid-July. By the time all this was going on, certainly, the world’s attention was being devoted to the second, and more widely anticipated, of 1910’s Great Comets (which, among other things, is the subject of a future “Special Topics” presentation).

More from Week 5:

This Week in History Special Topic Free PDF Download Glossary

Ice and Stone 2020 Home Page