Piers Bizony is an accomplished science journalist, space historian and documentary film maker. His books have explored the enormity and spectacle of the Universe as well as focused all way down to the sheer emptiness of a single atom. In his 2017 book Moonshots, Bizony takes readers on a photographic journey of 50 years of American space exploration, but with a twist. Nearly all of the 200-plus images were captured with Hasselblad cameras. How the cameras of a Swedish manufacturer came to be the defacto cameras used by the American space program is a story within the grander narrative of space exploration.

Wally Schirra took his personal Hasselblad camera with him on the solo Mercury 8 mission in 1962. It was those images that helped convince NASA of the importance of space photography for both scientific purposes and public relations. The later Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs all were documented with cameras from the Swedish manufacturer. It was a trio of Hasselblad cameras that were taken by Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins on the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission. Despite the wide temperature ranges and greatly reduced gravity, the Hasselblad cameras worked flawlessly to document the historic mission. Even more impressive is that Armstrong had the camera attached to his chest throughout the lunar excursion, a setup that had never been tested in space.

The Hasselblad utilized by Collins aboard the Columbia command module was brought back to Earth, however, the cameras (minus their film cartridges) used by Armstrong and Aldrin were left on the Moon’s surface in order to conserve weight on the return ascent. The Hasselblad remain on the Moon to this day.

Moonshots is not Bizony’s first book about space exploration. He previously authored Starman, Space Shuttle: Celebrating Thirty Years, One Giant Leap: Apollo 11 Remembered, The Rivers of Mars, New Space Frontiers, and The Man Who Ran the Moon. He also was a producer on a British television documentary that charted the making of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

We recently had the opportunity to satisfy our curiosity by asking Bizony a few questions about Moonshots, his thoughts on space exploration and his love for the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey.

RocketSTEM: How did researching and writing Moonshots differ from the previous books you’ve published about space exploration?

Piers BIZONY: “It was the first time that I ever created a book in specific response to something by another author and editor, namely, Michael Light, whose book Full Moon inspired me 20 years ago. Michael deliberately chose the landscapes of the Moon as his subject, so I wanted to focus more on the astronauts and the hardware aspects of Apollo as a companion volume.”

RS: During your research were you able to learn more about Wally’s camera? What was it about the Hasselblad cameras that made them nearly ideal for handling by astronauts and for the wide variety of photographic subjects – astronauts, spacecrafts, Earth and the Moon?

BIZONY: “Interestingly, NASA had not thought very much about the impact that pictures taken in space would have on the general public. There was so much focus on beating the Soviets into space, and ensuring the astronauts’ survival, at first the question of cameras was almost an afterthought. Schirra saw a Hasselblad in a camera store, and noticed its two overwhelming advantages. First, despite its handy size, it used quite a big frame in comparison to a 35mm camera, so the detail it could capture would be good, and secondly, the film magazine was a separate component from the main camera, so there was no question of having tom load film rolls. Instead, each mission would simply take several preloaded cassettes (or in the case of certain Apollo missions, lots of casettes). And you could swap film mid-shoot, without spoiling any frames or wasting any film. This turned to be a very useful feature for space.”

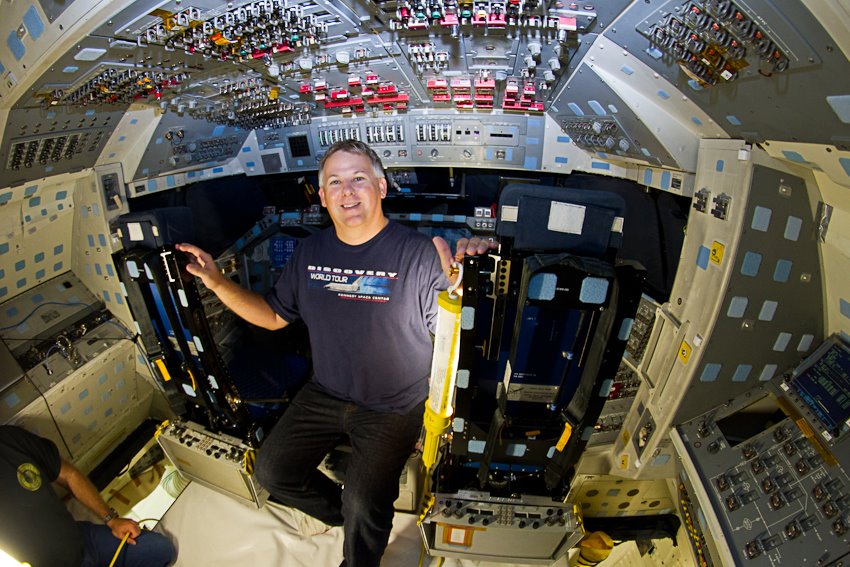

RS: The Carl Zeiss lenses have superb sharpness. Some of the pictures focusing on the instrument panels of the spacecraft are amazingly detailed. What made them so special and were these lenses exclusive to the Hasselblad cameras?

BIZONY: “See above answer, but of course the Zeiss lenses have always had a reputation for sharpness. But those pictures of instrument panels and so on often are blurry, because it turned out that the Hasselblads were difficult to use in close focusing mode because the space ones did not have viewfinders (the astronauts wouldn’t have been able to use focusing viewfinders while wearing their space helmets). The Hasselblads were best when set to medium range or infinity. The best interior shots of an Apollo mission were taken by the crew of Apollo 17, which carried a 35mm camera as well as the Hasselblads. And that crew could use the 35mm inside the modules, with their helmets off, so they could focus normally.”

RS: What was the process you had to go through in order to obtain access to the original images? How has NASA been safeguarding the original negatives for all these years?

BIZONY: “The first few months was all about arranging access, getting past the modern American government obsession with security, and basically, doing all the paperwork that would get inside NASA. After that, they were brilliant and very kind and helpful. But there are also many exceptional ‘citizen archivists’ who have done remarkable image archiving and restoration work, and Moonshots wouldn’t have been possible without their (properly credited) support.”

RS: You quote Ansel Adams in the book saying “A negative is comparable to a composer’s score. Each performance differs.” How did you go about having the original images scanned for the book? Did decisions have to be made about adjusting the images – such as color, contrast and sharpness?

BIZONY: “So far as I know, NASA hasn’t allowed more than a tiny handful of experts access to the ‘original’ flown film rolls, which are kept in cold storage, and are regarded as heritage items of the utmost value and fragility. Instead, books such as mine obtain access to first-generation positive transparencies, but even when these are in good condition they still need careful colour management after half a century.”

RS: A lot of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo astronauts have spoken about their perspective of the Earth and of humanity having changed once they saw the planet from LEO and beyond. When the first images of the Earth were released to news media by NASA, the U.S. was witnessing the rise of the hippie counter-culture movement while the country’s military was engaged in an unpopular war in Vietnam. Do you feel that these images of the Earth helped fuel a greater understanding at the time that we are all one world, one people?

BIZONY: “Without question, Apollo crews looking back at the distant earth had a huge impact on our environmental awareness. Apollo 8 crew member Bill Anders commented after his famous 1968 lunar orbiting mission, “We went all the way out there to explore the Moon, and what we discovered was the Earth.”

“This brings us neatly to what I think space exploration is all about. I have a problem with some modern space fiction films, such as Interstellar, or the Netflix reboot of Lost in Space, because space travel should not be about trying to escape from an Earth ravaged by our stupidity. These shows are great entertainment, but I do think we have to look after this planet, and space travel really is about getting that fact into perspective, even if we do get to explore lots of other worlds, too. But you can’t relocate seven billion people and all our animals and plants to another planet.”

RS: Even to this day, there seem to be few images that have surfaced from Russian cosmonauts during the early days of space exploration. Did Russia just never realize the value of such imagery?

BIZONY: “Russia was very keen not to reveal its hardware to Western eyes, so they were very secretive. That was just the culture of the Soviet world. They didn’t feel the same need as NASA did to promote their missions with glossy PR. They didn’t have to satisfy any tax payers that the money on space was worthwhile, because they were not operating in a democracy!”

RS: Because of the openness of the U.S. space program – both in success and failure – did the remainder of the world develop more interest and feel like NASA’s accomplishments belonged to all the people of the world?

BIZONY: “Yes I think so. Most people would associate Apollo, or the Hubble Space Telescope, as a ‘human’ achievement in general, and not just as NASA triumphs.”

RS: Our robotic explorers of the solar system have returned some incredible images of our neighboring planets, the Sun, other moons and comets and asteroids, even the demoted Pluto. Meanwhile the Hubble Space Telescope has secured its position as the most valuable astronomy instrument of all time. Yet the images taken during the manned expeditions have that little extra something that makes them even more special. Can you identify what it is about boots-on-the ground exploration that makes it so important to once again send humans beyond LEO?

BIZONY: “As Arthur C. Clarke has written: ‘One day we will not travel in spaceships. We will be spaceships.’ In a sense we already are. Robot probes are extensions of our minds and our physical reach, allowing us to scrabble in the soil of far-distant worlds with remotely operated claws. Does that mean, then, that we no longer have to go to the trouble of turning up in person to clutch handfuls of alien dust in our own hands? This has been the great debate ever since the Space Age began. Logic suggests that machine probes are the safest and most cost-efficient tools for space exploration. Instinct and emotion cause many of us to think differently. We want to know that we are seeing things in space from the perspective of other human beings, no matter how smart our robots become.”

RS: The emergence of commercial space activities was the focus of two of your books in the past 10 years. We’ve been tantalizing close to the realization of everyday civilians – albeit wealthier than most – rocketing to the edge of space for a few years, yet still are a tad short of that being reality. Have the delays been a surprise to you? Do you one day hope to experience weightlessness on a suborbital or orbital flight?

BIZONY: “Yes, everything has taken at least five years longer than I thought it would, but if SpaceX’s Crew Dragon vehicle works as planned, things could pick up very fast from now on. i would love to go into earth orbit, and even take a look at the Moon, but a trip to Mars would scare me. Space is infinite, but so far we can only travel through it in claustrophobic little tin cans. I wouldn’t fancy being cooped up for months, or even years, at a time.”

RS: You’re widely accredited as having written the authoritative reference book to the Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. What is about the movie that has so drawn your creative and intellectual attention over and over again throughout your life?

BIZONY: “2001 is so many things. It’s an art movie with unprecedentedly brilliant composition of every single shot, without exception. It’s a philosophy film, and it’s got the most realistic spaceships ever seen prior to the modern digital age. What’s not to love? The editing and music are extraordinary, and the movie makes very few concessions in a bid to win friends. It stands just as it is – monumental, sometimes unapproachable, but always awe inspiring. I was just one of zillions of kids who saw that and immediately wanted to rush out and by a camera and do something like what I’d just witnessed. No wonder 2001 is hugely loved by most film directors! The only problem with 2001 is that it spoiled me for Star Wars, which I just found incredibly silly in comparison. Only now, as a middle-aged (ahem!) film fan have I come to appreciate the original “Star Wars” for its innocence and sense of adventure.”

RS: Your books have covered everything from the grandeur of the Universe down to the emptiness of the tiny atom. You even authored Science: The Definitive Guide which provides readers with an overview of all the branches of science. Why tackle such an expansive project?

BIZONY: “I pitch a book because I want publishers to pay me to go and satisfy my curiosity. it’s a way for me to get an education, with a reasonably profitable kind of ‘student grant’ thrown in!”

RS: A few years back you authored The Search for Aliens. It seems nonsensical that we would be the only intelligent life in the entire vastness of the Universe. Do you think we’ll find microscopic life elsewhere within the solar systems in the coming decades? Do you think humanity has reached a level that alien lifeforms would be interested in communicating with us yet?

BIZONY: “That’s a big question, and it can only really be answered by making some tangible scientific discoveries. It would be really weird if no life existed anywhere else. we already know that the molecular building blocks of life are, literally, universally available. But as for intelligent life? They would have to be at exactly the same stage of technical and social evolution as us if we were going to establish a dialogue. The universe is 13.75 billion years old, and we humans have only been tinkering with advanced technology for a very few decades. The chances of a lucky conversational overlap between ‘us” and “them” seem very small, but I live in hope … On the other hand, I would be amazed if we didn’t find bugs or simple life somewhere one day soon.”

RS: Elon Musk is so obsessed with establishing a colony of one million people on Mars that he formed SpaceX. Meanwhile Jeff Bezo’s Blue Origin has been making great strides in relative secrecy. What do you think of these privately funded efforts to expand human exploration beyond LEO? Do you think the first bootprints on Mars will be placed by privately-funded colonists or by explorers sent by the United States, Russia, China, India or Europe?

BIZONY: “My major worry is that these private companies don’t publicise the nature of their hardware, nor report openly on problems. Apart from that, ‘Go, Elon!’ Not sure about Virgin Galactic, though. It feels as if investment is lacking, and progress is painfully slow. What must all those passengers feel who put down deposits more than a decade ago? Even so, the recent test flights have been spectacular.

“Mars is a long way off for human explorers. we don’t yet know how to get there, how to survive once we’ve got there, or how to come home. The Moon, on the other hand, is a great training ground for these missions, and it’s only three days flight time away. The moon is where the action will be for the next few decades. Humans on Mars is a fantasy for probably a half century. but Elon could prove me wrong, yet again! I once wrote that his plans for vertical landing rockets coming back down to earth were an impractical idea. Now you see SpaceX nonchalantly landing these things – and just as nonchalantly losing the occasional one, too. They have a healthy attitude to the challenges of space development!”

Featured Book: ‘Moonshots’

Fifty years after NASA astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped off the Eagle Lunar Module onto the lunar surface, the book Moonshots by Piers Bizony brings that era of space exploration to life thanks to the images produced by the Hasselblad cameras universally favored by the NASA astronauts.

Fifty years after NASA astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin stepped off the Eagle Lunar Module onto the lunar surface, the book Moonshots by Piers Bizony brings that era of space exploration to life thanks to the images produced by the Hasselblad cameras universally favored by the NASA astronauts.

Author Piers Bizony spent months sorting through the red tape of NASA bureaucracy in order to obtain access to positive transparencies of the original film negatives, which were then methodically analyzed and color-corrected by experts in order to faithfully reproduce them within the book.

Moonshots presents more than 200 incredible photos of NASA spacecraft, the Earth, the Moon, and the astronauts themselves at work beyond the confines of the Earth. Pulled from the agency’s archives, the images cover the Gemini, Apollo and Space Shuttle programs, including milestones such as the six Moon landings, Skylab, the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, servicing of the Hubble Space Telescope, and the construction of the International Space Station.

The large format book is as hefty as the material presented inside it. Our review copy was the hardback edition with the slipcover. It is 12 1/4 x 12 1/4 inches and weighs six pounds. That’s considerably less than the 47 pounds of Moon rocks collected by Armstrong and Aldrin, but still a weighty tome for any Earthbound reader.

Many of the high-resolution images reproduced within Moonshots have rarely been seen with such vibrancy and sharpness. Some readers may even forget they are stuck on terra firma and instead start to believe that they are really in orbit or on the surface of the Moon witnessing these cosmic views with their very own eyes.

As easy as it would have been to let the photos be the entire focus of the book, Bizony didn’t slack in his writing duties. This visual chronicle of space exploration is complemented with a rich narrative. Bizony’s curiosity is evident throughout as is his adept execution at sharing his knowledge of the subject. From how the original images have been safeguarded by NASA, to the debate of human versus robotic exploration, to the enlightenment nearly every astronaut experienced when seeing the whole of the Earth from deep space, the writing expertly guides the reader through the 240-page spotlight on American space exploration.

Ad astra per litterarum!

Praise from others

“Moonshots provides some of the most beautiful, high-quality imagery I’ve ever seen to accompany humanity’s amazing story of reaching the stars through ingenuity, perseverance, and curiosity. I highly recommend adding it to your collection.”

— Astronomy.com

“The book is awesome, a fabulous celebration of space-faring, highlighting NASA’s greatest achievements, and enriched by the sheer size and resolution of the film frames”

— Mature Times

“Moonshots comes encased in a heavy-duty slipcover, the better to protect the book’s beauty from dings and fading. Both space fans and photography buffs will like this book.”

— SkyandTelescope.com

Review book details

Hardcover: 240 pages

Publisher: Voyageur Press (October 1, 2017)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 0760352623

ISBN-13: 978-0760352625

Goodreads’ Rating Details: 5