Titan, Europa, Io and Phobos are just a few members of our solar system’s pantheon of moons. Are there are other moons out there, orbiting planets beyond our sun?

NASA-funded researchers have spotted the first signs of an “exomoon,” and though they say it’s impossible to confirm its presence, the finding is a tantalizing first step toward locating others. The discovery was made by watching a chance encounter of objects in our galaxy, which can be witnessed only once.

“We won’t have a chance to observe the exomoon candidate again,” said David Bennett of the University of Notre Dame, Ind. “But we can expect more unexpected finds like this.”

The international study is led by the joint Japan-New Zealand-American Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA) and the Probing Lensing Anomalies NETwork (PLANET) programs, using telescopes in New Zealand and Tasmania. Their technique, called gravitational microlensing, takes advantage of chance alignments between stars. When a foreground star passes between us and a more distant star, the closer star can act like a magnifying glass to focus and brighten the light of the more distant one. These brightening events usually last about a month.

If the foreground star – or what astronomers refer to as the lens – has a planet circling around it, the planet will act as a second lens to brighten or dim the light even more. By carefully scrutinizing these brightening events, astronomers can figure out the mass of the foreground star relative to its planet.

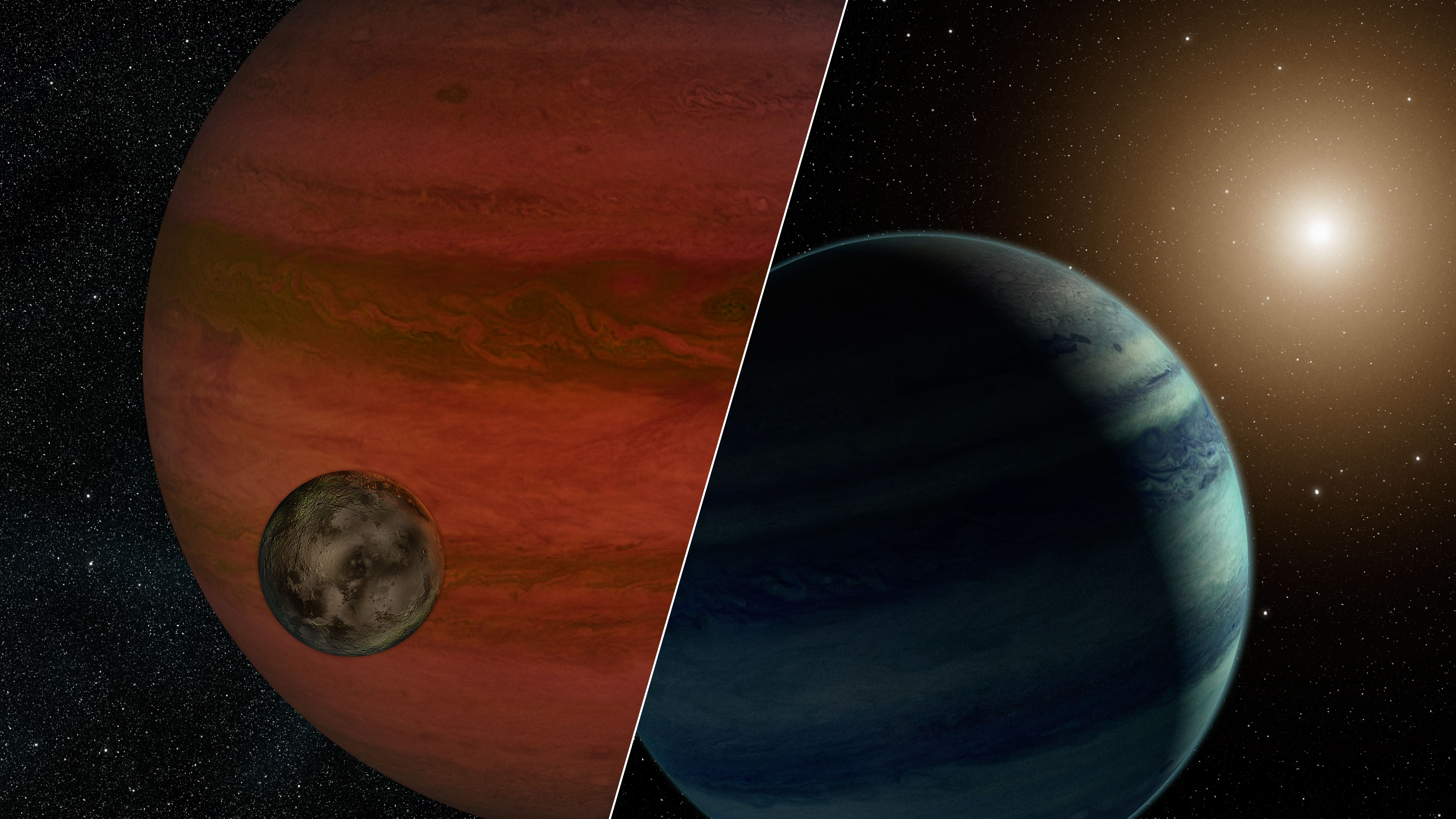

In some cases, however, the foreground object could be a free-floating planet, not a star. Researchers might then be able to measure the mass of the planet relative to its orbiting companion: a moon. While astronomers are actively looking for exomoons – for example, using data from NASA’s Kepler mission – so far, they have not found any.

In the study, the nature of the foreground, lensing object is not clear. The ratio of the larger body to its smaller companion is 2,000 to 1. That means the pair could be either a small, faint star circled by a planet about 18 times the mass of Earth — or a planet more massive than Jupiter coupled with a moon weighing less than Earth. The problem is that astronomers have no way of telling which of these scenarios is correct.

The ground-based telescopes used in the study are the Mount John University Observatory in New Zealand and the Mount Canopus Observatory in Tasmania.

Additional observations were obtained with the W.M. Keck Observatory in Mauna Kea, Hawaii; European Southern Observatory’s VISTA telescope in Chile; the Optical Gravitational Lens Experiment (OGLE) using the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile; the Microlensing Follow-Up Network (MicroFUN) using the Cerro Tololo Interamerican Observatory in Chile; and the Robonet Collaboration using the Faulkes Telescope South in Siding Spring, Australia.